Liz Magor at MOCA: “The Separation”

What about all the forgotten items? What about the stacks of coffee lids, the candy wrappers, the plastic bags in soft pastels, the crenillated foil cups, and sparkly bits of paper stuffed in a gift bags, the trays — presenting so many things! — artfully coated in silver or gold? What about the big gulp holders — the really big ones — with plastic straws poking out the top? What about the hard — infuriating, practically unbreakable — plastic encasements for purchased items? What about the cigarette butts, the liquor bottles, the beer cans, the unwanted toys, empty bottles, scattered gravel, moldy cookies, moth eaten blankets, matted fake fur, dead animals, shells, gum, junk, garbage, trash?

We’re talking about the metier of Liz Magor, in her exhibition titled The Separation, on view at MOCA.

On entering the exhibition the viewer is faced with an expanse of shiny, hard mylar boxes. The boxes are brightly lit from above. They sparkle. They attract.

The lighting fixtures are kind of hilarious and create a bit of a fun house atmosphere.

I wander through the box array, anticipating. I don’t know what exactly — but something — something that is going to be exciting, in some way. And that is where everything starts to slow down.

Liz Magor presents the material that slips by us moment to moment, all the stuff that we ignore. As she does that, we are obliged to consider a lot of things, but mostly transience and permanence, and, as strange as it may sound, the whole idea of time rushing by.

Many of her sculptures, protected in their big, clear boxes, are casts of the original objects they represent. They are facsimiles, removed from their original function, context and incidental narrative, to exist in another realm altogether. Maybe that’s what she is referring to in the exhibition title (“The Separation.”) She has removed these bits of our material lives and “separated” them from their predictable stream of existence.

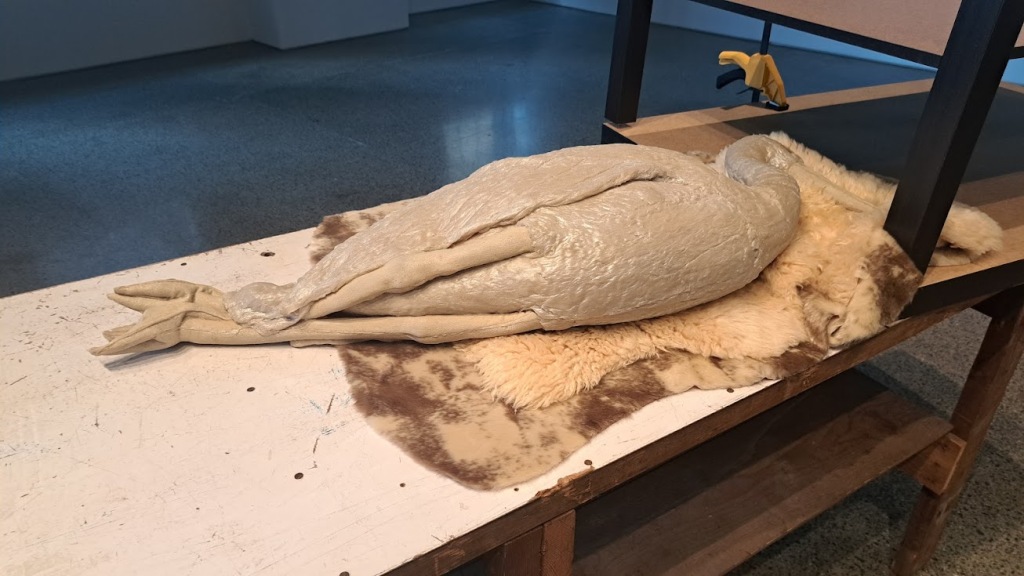

There are a few structures on the pheriphery, — hammered together Ikea and antique, worn work tables — holding cast sculptures of stuffed (or sometimes just dead) animals, lying in sympathetic poses, insisting on our attention.

(In fact, I may have won this lion creature, above. It was some years ago, at the ex, prior to the pandemic. Yes, it was a shooting game! Oh god, look at him now.)

There are lots of video’s online featuring Liz Magor talking about her work. She has a very calm, amused presence, although she always seems to be talking about being a “worrier.”

Something I got from watching one of the videos is her connection to minimalism. She is drawing our attention to particular objects. Don’t start looking for some allegory, metaphor or moral. She’s not hectoring us about being consumers, urging us the Save the Whales, or read Wittgenstein. She’s all about: “What you see is what you see,” as Frank Stella famously said.

The videos are worthwhile. I definitely liked watching her make stuff and talk about her interest in death.

Liz Magor at Susan Hobbs: “Style”

More work by Liz Magor can be seen at Susan Hobbs. The show, titled “Style,” is really beautiful and concise, comprised mainly of clothes slightly eaten by moths. Found objects — mostly stuffed animals, also possibly moth eaten — attend the garments, embrace them and present them for our viewing.

The gallery has helpfully provided some instructions on dealing with moths. I know from experience this has been a problem over the past few years in my Toronto neighborhood.

Clean your closet, combine sunlight with vigorous brushing, heat-treat woollen items in an oven set to the lowest heat, freezing (but only if the change from warm to cold is abrupt) for at least 72 hours, hide the rest of your clothes in compression bags. In executing some of the solutions above, the garment is stripped of its function and tended to as an object that needs our intervention. Our attempt to fix the problem only adds to our conception that we hold control, but all things have a lifespan with and without us.

from Susanhobbs.com

The artwork of Liz Magor strikes me as so efficient! As in “The Separation” at MOCA, in viewing “Style” we are obliged to consider the limits of our possessions, the past and future of our prized wearable items, and so too of our own limits. Hmmmm.